Audio for this story from All Things Considered will be available at approx. 7:00 p.m. ET

October 14, 2012

Fifty years ago, the United States stood on the brink of nuclear war.

On Oct. 16, 1962, the national security adviser handed President John F. Kennedy black-and-white photos of Cuba taken by an American spy plane. Kennedy asked what he was looking at. He was told it was Soviet missile construction.

The sites were close enough â€" just 90 miles from the U.S. â€" and the missiles launched from there could reach major American cities in mere minutes.

The Cold War was heating up to a near-boiling point.

For a two-week period, Kennedy consulted with his closest advisers about what to do. Today, we know what they said because the president had a secret tape recorder rolling â€" but back then, why did Kennedy order the secret recordings?

"We don't really know," Stacey Bredhoff tells weekends on All Things Considered guest host Celeste Headlee. "Some historians think it's because he wanted them to help him write his memoirs. Others say he just wanted a very accurate record for history of what was actually said."

Bredhoff is curator at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston. She is heading up an exhibit at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., showcasing the recordings as well as documents and artifacts from the Cuban missile crisis.

The president's group of advisers would later be known as the "Ex Comm," short for the Executive Committee of the National Security Council. While they conferred, the stakes kept mounting.

A map prepared by the CIA shows areas and cities within range of nuclear missiles launched from Cuba in October 1962.

"At one point the president says, 'Time ticks away on us,'" Bredhoff says. "Because with each passing moment, those missile sites are getting closer and closer to being fully operational. And that's what the president wanted to avoid."

Kennedy heard a range of opinions about how to respond.

George Ball, undersecretary of state, urged restraint.

"A course of action where we strike without warning is like Pearl Harbor," he says in the recording. "It's the kind of conduct that one might expect of the Soviet Union. It is not conduct that one expects of the United States."

But Bredhoff says others, particularly Air Force Chief of Staff Curtis LeMay, almost bait the president, "just falling short of calling him a coward for not taking direct, quick military action."

"I think that a blockade and political talk would be considered by a lot of our friends and neutrals as being a pretty weak response to this," LeMay says. "And I'm sure that a lot of our own citizens would feel that way, too."

Four days after learning about the missile sites and meeting daily with the Ex Comm, Kennedy had made up his mind.

He ordered a military blockade of ships to surround Cuba. This so-called quarantine would keep the Soviets from bringing in any more military supplies.

That same day, Kennedy came clean to the nation about what was happening. Oct. 22, 1962, marked the first time the president spoke publicly about the missile crisis.

"My fellow citizens, let no one doubt that this is a difficult and dangerous effort on which we have set out. No one can see precisely what course it will take or what costs or casualties will be incurred," Kennedy says in the televised speech.

There was a single combat casualty. On Oct. 27, Air Force pilot Maj. Rudolf Anderson Jr. was shot down during a reconnaissance mission over Cuba.

Maj. Rudolph Anderson Jr. was shot down and killed over Cuba during the October 1962 crisis.

But overall, Kennedy's strategy was a resounding success.

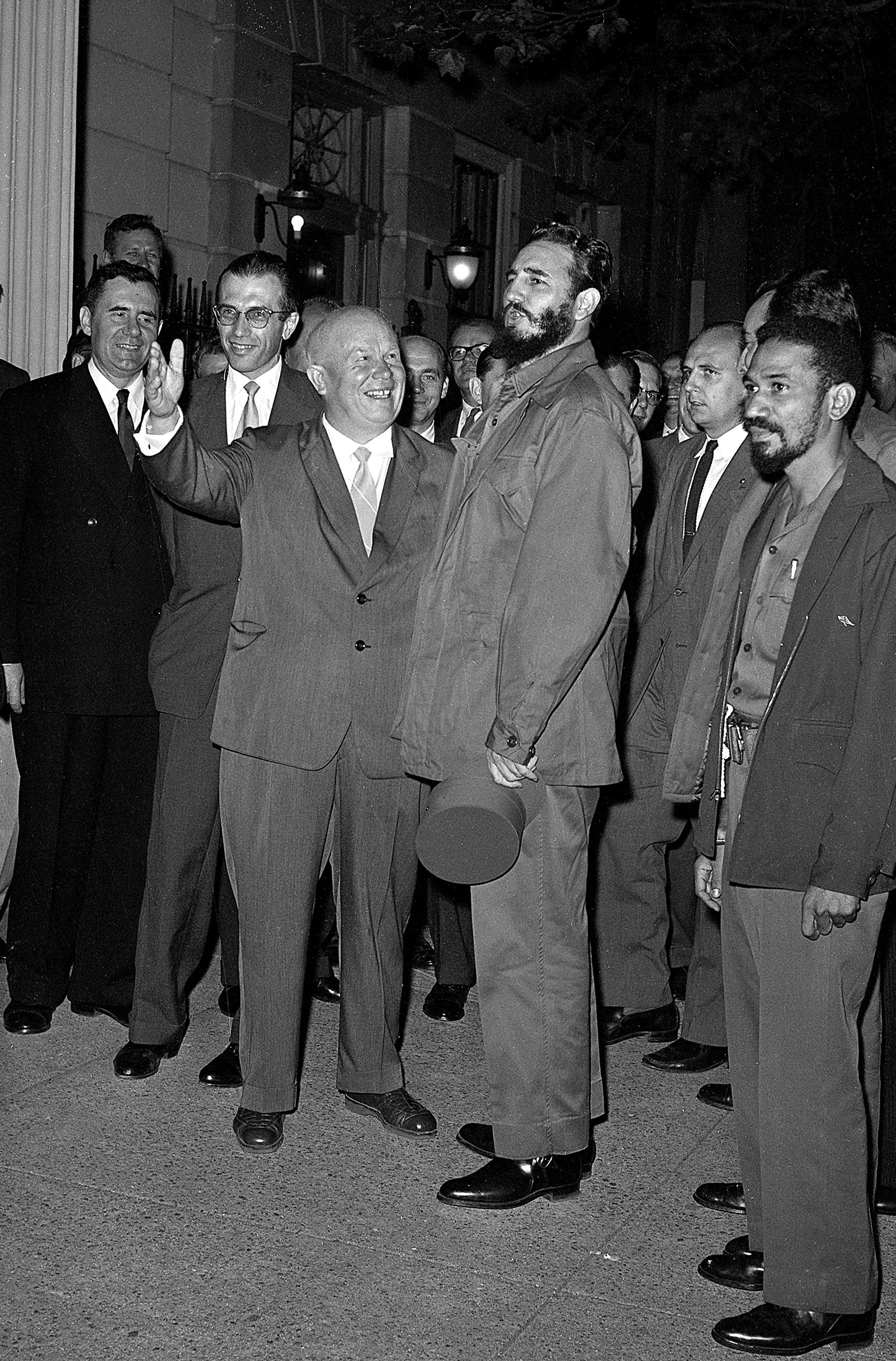

Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev made a deal. The Soviets dismantled their weapons site in Cuba. In exchange, the U.S. pledged to never to invade Cuba. And in secret, the U.S. agreed to remove all of its missiles from Turkey, which bordered the Soviet Union.

"It's almost impossible to imagine the weight of the responsibility of the decisions that he was making," Bredhoff says of Kennedy. "But he was able to find a solution that was acceptable to Khrushchev, didn't humiliate his adversary and was able to step back."

We can be grateful for Kennedy's clear, disciplined thinking that pulled us back from the precipice, she adds.

"Half a century later, it's just a great time to look back with this perspective and with the wealth of historical resources that have become available in recent years and take a look at this moment in history, which was really one of the most dangerous moments in the world," Bredhoff says.

"To the Brink: JFK and the Cuban Missile Crisis" is open at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., through Feb. 3, 2013. It then moves to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston from April 12 through Nov. 11, 2013.